(S2 Ep.28) Interview to U Gambira (Saffron Revolution)

A Monk’s Story of Courage, Compassion, and Resistance

TheGentleLaw Community

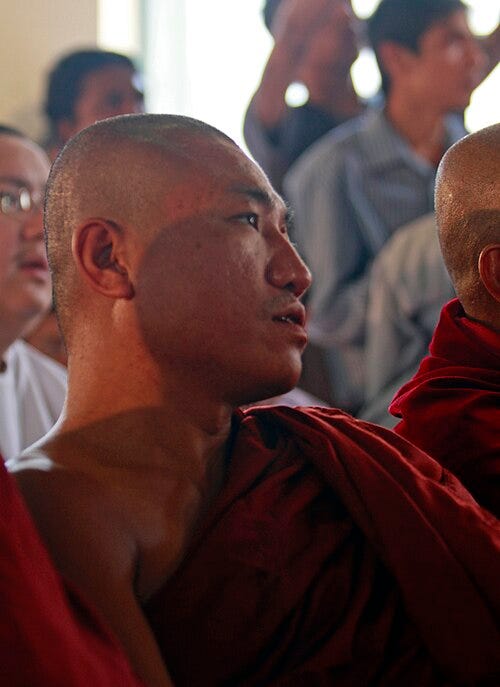

In 2007, the streets of Myanmar were filled with an ocean of saffron robes. Thousands of Buddhist monks led peaceful protests against a brutal military regime, chanting verses of loving-kindness even as they risked imprisonment, torture, or death. Known globally as the Saffron Revolution, this extraordinary movement captured the world’s attention—not only for its courage, but for its moral clarity.

Among its leaders was U Gambira, a young monk whose voice and vision helped organize the All Burma Monks' Unions Alliance and guide the peaceful resistance. But his story began years earlier, as a novice monk building underground networks, and it continued long after the protests ended—through arrests, torture, exile, and eventual resettlement in Australia.

Here is my interview:

Can you share your personal experiences during the Saffron Revolution? What inspired you to get involved?

The Saffron Revolution began in September 2007, but my involvement started long before that. As a young novice monk in 2004, I helped form underground monk networks that would later play a key role in the movement. At that time, I couldnt have imagined the scale it would reach. When it finally unfolded, it became a powerful and historic movement led by the Sangha.

During the revolution, I was in Mandalay, while our underground monk network's main office was based in Yangon. On September 3rd, 2007, I traveled to Mandalay to meet with local monk leaders and organize strategy sessions. On September 4th, we held a successful meeting at a monastery in the Kywe Se Kan neighborhood, where various monk groups agreed to work together.

On September 5th, I received news that in Pakokku, members of the monks' alliance I had helped form in 2006 were marching in protest. That evening, two monks were arrested and brutally beaten by soldiers and police. This marked a turning point. In response, I called an emergency meeting in Mandalay on September 7th. We released public statements condemning the actions, which were broadcast by VOA, RFA, DVB, and BBC.

By September 9th, we had unified underground monk networks across Upper and Lower Myanmar into the All Burma Monks' Unions Alliance (ABMUA). Immediately after its formation, we released a statement with four key demands addressed to the ruling military junta. Since the regime failed to respond, monks and civilians began staging peaceful processions across the country starting on September 17th.

On September 18th, all monks within and outside Myanmar observed a symbolic act of protest at exactly 12 PM Myanmar Standard Time, known as the Patta Nikkujjana Kammas, which involved boycotting alms from members of the military. Daily processions of monks and civilians reciting the Metta Sutta (Buddha's discourse on loving-kindness) followed in many cities.

I stayed in Mandalay to continue coordinating, issuing daily statements which were broadcast by international radio outlets. On November 4th, 2007, I was arrested by military intelligence while traveling between Mandalay and Sintgu.

What inspired me to take part was my backgroundI was born into a politically active family. My father led the protests in Pakokku during the 1988 uprising, and my eldest brother was a student leader in Upper Myanmar. Both were imprisoned for their political activities. Additionally, I was raised in a family that valued reading and independent thought. Through literature and the Buddhas teachings, I developed a deep sense of justice and an aversion to tyranny.

What role did the Buddhist monastic community play in the protests? What impact did it have on the movement as a whole?

The monastic community played a central and symbolic role in the Saffron Revolution, contributing in two key ways. First, on September 18th, monks across the country observed the Patta Nikkujjana Kammas, rejecting offerings from the militarya rare and significant act. This was carried out independently by the monks, inside their monasteries.

Second, monks led peaceful processions in the streets alongside civilians, chanting the Metta Sutta. This combination of spiritual discipline and public protest gave the movement moral authority and inspired widespread participation. The peaceful nature of the marches sent a powerful message grounded in compassion and nonviolence.

How did the military government respond to the monks' involvement, and what challenges did you face during that time?

The military regime responded with brutal forcelive ammunition, batons, killings, arrests, and imprisonment. Their violent crackdown on peaceful monks reciting teachings of compassion and nonviolence was shocking. One of our biggest challenges was that no one could stop the regimes aggression. The lack of protection for the peaceful monks underscored the gravity of our struggle.

How significant was the symbolic presence of the saffron robe in the revolution? How did it reflect unity and resistance?

The monks saffron robes became the visual symbol of the revolution. As long lines of monks marched peacefully in their identical robes, the color saffron came to represent unity, dignity, and moral resistance. This is why the movement became widely known as the Saffron Revolution. The uniformity of the robes emphasized solidarity among the Sangha and inspired unity among civilians.

Can you share a particularly meaningful moment or event from the revolution that had a lasting impact on you?

My personal story has been documented in the book "Naraka The U Gambira Story", written by my wife, Marie Siochana. I encourage you to read it, as it contains detailed insights and personal reflections that I hope will be valuable to you.

What was the role of laypeople in the revolution, and how did it affect broader Myanmar society?

Laypeople played a vital role in the revolution. Without weapons or violence, they marched side by side with monks, chanting the Metta Sutta and calling for change. This united front strengthened public opposition to the military regime. The revolution gave rise to a new generation of activists committed to ending military rule and advocating for democracy.

What successes did the Saffron Revolution achieve? Were there any major lessons learned from the experience?

The revolution brought international attention to the Burmese struggle and led to the imprisonment of over 2,800 political prisoners, which increased international pressure on the regime. In 2008, 2010, and 2012, political prisoners, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, were released.

A UN Special Envoy, Mr. Gambari, was appointed and visited Myanmar several times. Dialogues that had been hoped for over decades began to emerge. The military leaders hastily implemented the 2008 Constitution and began transitioning to a quasi-civilian government. Fuel and commodity prices, which had initially sparked the protests, were also adjusted.

The movement birthed a new generation of resistance. However, one painful lesson remains: nonviolent resistance alone cannot always defeat a brutal military regime.

How did your spiritual practice evolve during the revolution? Did it guide your actions?

During the revolution, I had little time for meditation, sleeping only four hours a night. However, the trainings I had received from 2004 to 2006 in Mae Sot, Thailand including Political Defiance, Community Organization, Leadership, and Human Rights helped prepare me to lead. I applied these lessons to build and coordinate the movement.

How do you view Myanmars current situation? What role can Buddhism play in its future?

Myanmar is currently engulfed in a civil war aimed at ending military dictatorship. People are suffering not just from war, but also from disease, natural disasters, and neglect. The international community has largely ignored Myanmar's plight, a severe moral failure. If Myanmar received even a fraction of the support given to Ukraine, the military regime could be swiftly defeated.

In the future, Buddhism will likely remain a strong moral and cultural force. However, in the immediate aftermath of the conflict, it may face many challenges and controversies.

Looking back, how do you reconcile activism with monastic life? What advice would you give to young monks or others struggling to balance their convictions with spiritual commitments?

Activism and monastic life may seem separate, but history demanded that we act. If we had remained silent, both monks and civilians would have suffered even more under military oppression.

My advice is this: If Myanmar becomes a democratic and just society, then monks can return to purely spiritual pursuits. But as long as tyranny remains, monks must stand up as responsible citizens to confront injustice, as history demands of them.

After the revolution, what led you to leave Myanmar, and how did you find your way to Australia?

After the revolution, I was repeatedly imprisoned and tortured physically, mentally, and through forced medication. I contracted malaria twice in prison, and my health deteriorated significantly. Eventually, I had to disrobe for medical reasons.

Soon after, I married Marie Siochana, an Australian citizen. Due to ongoing harassment and arrests by the military, Marie helped me apply for political asylum in Australia. My first application was rejected, but the second was accepted by the Australian embassy in Bangkok. I arrived in Australia as a refugee on March 13, 2019.

What were the biggest challenges in transitioning from monastic life in Myanmar to civilian life in Australia?

As a former monk, I didnt face any unusual challenges adjusting to life in Australia. It has been a normal experience overall.

How have your Buddhist practices helped you adapt to life in Brisbane and its cultural differences?

My Buddhist practices and teachings have been invaluable in helping me adapt. Teachings like the Mingala Sutta and Sigalovada Sutta are full of practical guidance not just for monks, but for laypeople navigating daily life. The Dhamma continues to be my foundation.

Can you describe your current life in Brisbane? Are you still practicing Dhamma? How are you contributing to the local Buddhist community?

I live on the outskirts of Brisbane in a large property. Because of the distance from the city and my busy schedule at home, I havent been in regular contact with the Burmese community or other friends for a while. However, I continue to live by the Dhamma and incorporate it into my daily life.

As a former Buddhist monk living in a multicultural society like Australia, how has your experience been? How do you balance the daily demands of social life in Brisbane with your monastic background?

Since I mostly stay at home and rarely go out, I don’t have much interaction with the local community. Instead, I quietly maintain my spiritual practices at home every day. My background as a monk continues to shape my lifestyle and values, even though I am no longer in the monastery. Living in a diverse environment like Brisbane requires inner discipline and adaptability, and I try to integrate my monastic teachings into this new setting as best as I can.

Have you been involved in any social or political causes in Australia, particularly those related to Myanmar or Buddhism? How do you stay connected to the struggles of your homeland?

In the earlier years after I arrived here, I used to go to downtown Brisbane every Saturday to deliver speeches and participate in protest events supporting democracy in Myanmar. However, since 2023, Ive been overwhelmed with domestic responsibilities and haven’t been able to go out as much. Still, I continue to support my homeland financially in whatever ways I can.

As a former monk from Myanmar, what kind of lessons have you learned living in Brisbane?

Here, I’ve observed that many people identify as atheists. I'm still in the process of understanding their way of thinking, living, moral values, and cultural traditions. Another notable difference is how distant family relationships can be. Unlike in Myanmar, where siblings and extended family live closely and support each other, here many people live apart, which I believe contributes to emotional hardship. In fact, Australia has one of the highest suicide rates in the world. I believe this is due in part to emotional isolation and the lack of close family support. In contrast, in Myanmar, family bonds are strong, and people often help one another through difficult times.

Are you planning to return to Myanmar, or are you focusing on building a life in Australia? How do you envision your future?

I do plan to return to Myanmar once the Spring Revolution comes to an end and peace is restored. Ive already discussed this with my wife, Marie Siochana, and she intends to move with me to Myanmar. We will continue to travel back and forth between Australia and Myanmar, but ultimately, I hope to return to the monastic life. I find deep joy and fulfillment in meditation, chanting, and sharing loving-kindness. My aspiration is to devote myself fully to this spiritual path once again.